Volume

What Is Trading Volume?

Trading volume refers to the total amount of an asset that has been actually traded (matched buy and sell orders) for a specific trading pair within a certain time period. It is a key metric to gauge market activity and liquidity.

On an exchange’s candlestick chart, colored bars below the price candles represent the trading volume for each corresponding period. The bar colors usually follow price movement, making it easier to visually identify surges or contractions in volume. For beginners, the most common reference is the “24-hour trading volume,” which summarizes market activity over the past day.

How Is Trading Volume Calculated? What Are the Differences in Units?

Trading volume can be measured either by the “quantity” of the asset traded or by its “monetary value.” Quantity-based volume is usually denoted in units of the asset, such as BTC; value-based volume is typically expressed in USD or USDT equivalent.

The choice of unit affects comparisons: For the same asset, when its price rises, quantity-based volume may appear smaller, while value-based volume could be amplified. It’s also important to distinguish between “single-exchange trading volume” and “aggregated market trading volume.” The former reflects trades on one platform; the latter aggregates data from multiple exchanges.

On-chain transfer data is not the same as trading volume. Transfers simply represent fund movements between addresses and may not involve matched trades, so their meaning is entirely different.

What’s the Difference Between Trading Volume and Trading Amount?

Trading volume emphasizes the “quantity” traded, while trading amount (often called “turnover”) highlights the “monetary value.” Many interfaces combine both, displaying “24h trading volume (USD equivalent),” which is essentially value-based.

When reading charts, first check the platform’s labeling: If it says “Volume: 1,000 BTC,” that’s quantity-based; “Volume: $50M” indicates value-based. Both are useful—use value-based for comparing across different assets, and either metric for historical analysis of a single asset.

What Market Signals Does Trading Volume Reveal?

Trading volume reflects the level of participant engagement and the strength of trading intent. Volume surges often occur at key price levels, while contractions are typical during consolidation or indecisive periods.

- Trend Strength: In uptrends, rising prices accompanied by moderate volume growth and lower volume on pullbacks are considered healthy. If prices rise while volume consistently shrinks, the trend may be weak.

- Liquidity: High trading volume generally means better liquidity and lower slippage. Liquidity refers to how easily you can trade near the current price.

- Volatility Potential: Around major news events, trading volume often spikes, signaling potential market shifts.

How Is Trading Volume Used in Breakout Strategies?

Volume is critical for confirming breakouts—the core principle is that price and volume should move together. When price breaks above previous highs or key resistance levels on increased volume, the breakout is more likely to continue; if there’s little or shrinking volume, false breakouts are more probable.

Step 1: Identify key levels, such as previous highs, trendlines, or channel resistance.

Step 2: Compare the breakout candle’s volume to the recent average (ideally well above the last 20–50 candles).

Step 3: Manage risk—if price falls back below the key level after a breakout with increasing volume, this may indicate failure and require a timely stop-loss.

Example: On Gate’s spot chart, if price closes above channel resistance with a volume bar much higher than the two-week average, and subsequent retests have lower volume without breaking down, continuation is more likely.

How Can Trading Volume Be Combined With Other Indicators for Reliability?

Combining trading volume with other popular indicators reduces subjective bias:

- Volume Weighted Average Price (VWAP): VWAP calculates the average price weighted by trading volume, approximating the average entry cost of most participants. A price above VWAP with strong volume supports trend strength; a drop back below VWAP with heavy selling may indicate trend weakness.

- On-Balance Volume (OBV): OBV adds daily volume on up days and subtracts it on down days to form a cumulative line. If price reaches new highs but OBV doesn’t, this may signal a divergence and weakening trend momentum.

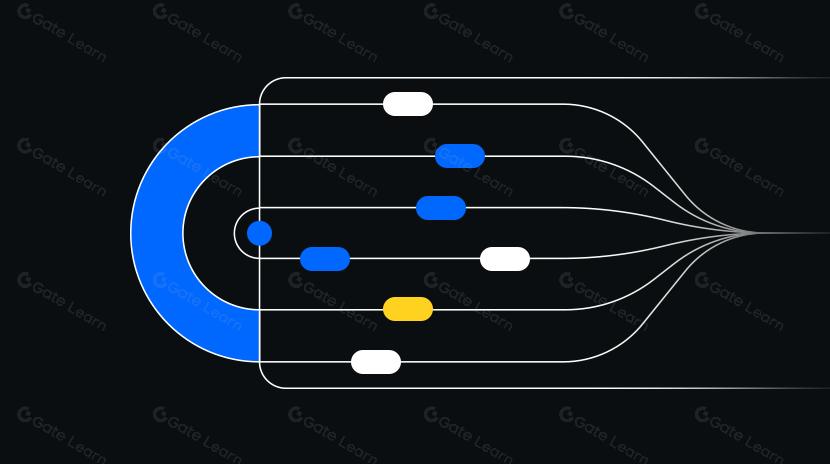

- Volume Profile: This shows cumulative trading volume at various price levels, forming “high-volume nodes” and “low-volume nodes.” Prices can move quickly away from low-volume zones but may consolidate near high-volume areas.

Always use these indicators in context. Never rely on a single signal—combining them with support/resistance and broader market rhythm yields more reliable results.

How Does Trading Volume Differ Between Spot and Derivatives Markets?

Spot trading volume represents actual asset purchases and sales, reflecting long-term position changes. Derivatives trading volume measures contract turnover; with leverage, large volumes are more common. Because of leverage, derivatives markets’ trading volumes are more sensitive to short-term volatility.

As of 2025, derivatives markets often have higher volumes than spot markets in many periods, driven by leverage and hedging needs. When analyzing derivatives volumes, also track open interest—the total number of open contracts—to distinguish between turnover and new capital entering.

How Do On-Chain and Exchange Trading Volumes Align?

On-chain data tracks transfers between addresses and smart contract interactions—not matched trades. Therefore, “on-chain transfer volume” and “exchange trading volume” are fundamentally different. Decentralized exchange (DEX) volumes are derived from on-chain data but must still be distinguished from self-transfers between addresses versus actual trades.

To align metrics:

Step 1: Decide whether you’re analyzing “trading activity” or “capital flow.” Use exchange volumes for trading activity; use large on-chain transfers or active addresses for capital flow.

Step 2: Compare like-for-like metrics—don’t directly compare on-chain transfer volume to centralized exchange trading volume.

Step 3: Exclude short-term anomalies; focus on multi-day moving averages to avoid misinterpretation from large single transfers.

What Are the Risks and Pitfalls of Trading Volume? How Do You View It Correctly on Gate?

Main risks include differences in definitions and potential manipulation. Some markets may engage in wash trading—showing consistently high or illogical volumes, or sudden spikes without price movement. Relying solely on trading volume can ignore order book depth and slippage risks.

To correctly view and use trading volume on Gate:

Step 1: Select a trading pair and open its candlestick chart; the default bottom panel shows trading volume bars. Adjust timeframe to match your strategy (e.g., 1-hour or 4-hour).

Step 2: Add indicators like VWAP or OBV alongside trading volume. Mark key price levels and compare breakout candle volumes to the average over the last 20–50 candles.

Step 3: Check both buy/sell order books and depth to assess liquidity. If trading volume isn’t low but depth is thin, slippage risk remains high. Use limit orders and scale entries to control costs.

Security tip: Any decision based on trading volume can fail—always combine it with stop-loss, position sizing, and contingency planning to avoid over-reliance on one metric.

Key Takeaways on Trading Volume

Trading volume is a fundamental metric for measuring market activity and liquidity—it can be tracked by both quantity or value. Understanding it requires distinguishing between quantity vs. value, spot vs. derivatives, and on-chain vs. exchange definitions. In practice, trading volume helps confirm trends and breakouts but should be combined with VWAP, OBV, Volume Profile, key price levels, and order book depth to avoid being misled by anomalous data. On Gate, use multi-timeframe analysis, indicator combinations, and strict risk management to identify actionable signals and control risk effectively.

FAQ

What Does High Trading Volume Indicate?

High trading volume means there are many active participants and strong buying/selling interest in the market. High volumes often accompany price breakouts or trend confirmations—signaling strong consensus—but keep in mind that high volume doesn’t always mean price movement is reliable; always analyze it alongside price action to avoid being misled by false surges.

Is Trading Volume the Same as Trade Count?

In crypto markets, “trading volume” and “trade count” are often used interchangeably but technically differ. Trading volume usually refers to either the number of executed trades or total units of an up asset exchanged; trade count sometimes specifically means number of transactions. On Gate and similar platforms, "trading volume" generally refers to asset quantity—a standard industry convention beginners should follow.

Why Does Price Sometimes Rise as Trading Volume Falls?

This phenomenon is known as “volume-price divergence”—often a warning that a trend reversal may be near. If prices rise but trading volume contracts, it signals weak buyer strength—possibly retail traders following momentum or institutions distributing holdings—indicating limited upward drive. Caution is advised; watch for follow-up buying or potential pullbacks.

How Can Beginners Quickly Judge if Trading Volume Is Normal?

Compare three timeframes: daily trading volume vs. its 30-day average; hourly trading volume vs. daily average; real-time trade speed vs. historical norms. On Gate’s candlestick chart, enable "volume" to see bar height changes intuitively. Only when trading volume jumps 2–3x above average does it count as a true surge; minor fluctuations are normal.

How Does Trading Volume Differ in Bear vs. Bull Markets?

In bull markets, trading volume typically rises steadily with moving averages trending higher—strong volumes accompany rallies. In bear markets, overall volumes shrink but sharp spikes may occur during panic selling. To identify market stages, focus on both "absolute level" and "directional trend" of trading volume—not just size alone—to avoid being misled by short-term rebounds.

Related Articles

Exploring 8 Major DEX Aggregators: Engines Driving Efficiency and Liquidity in the Crypto Market

What Is Copy Trading And How To Use It?